A recent social media meme pointed out the terrible irony of celebrating the Thanksgiving holiday at a time when Native Americans are being tear-gassed, shot with rubber bullets, and sprayed with water cannons in sub-freezing temperatures.

I would add two more words to describe that confluence – fortuitous and Eucharistic.

I realize the risk in both of those words just now, especially a Christian liturgical word that has carried so much colonial and neo-colonial baggage, a religious rite that traveled with conquerors and pioneers who scattered, decimated, and killed the native tribes on the very land those same tribes now seek to protect. I take this risk hoping the ongoing standoff at Standing Rock will inspire more communities to engage in courageous and decisive action at the intersection of racial history and ecological fragility.

I fuel this hope, especially at this time of year, by remembering that Christian faith began not with a text or a doctrine or an institution, but with radical social practice – table fellowship. As the gospel writers portray it, Jesus was constantly getting in trouble for eating with the wrong people.

Who sat at your table – and whose table you joined – mattered a great deal in that first century society, nearly as much as the character of your sexual relations. Both food and sex perpetuated hierarchies of social value, relations of power that stratified ancient Mediterranean communities just as they do today. Jesus cast these hierarchies aside – much to the ire and even revulsion of many in his own community; this eventually cost Jesus his life.

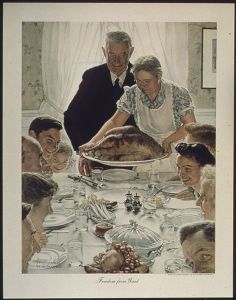

The earliest Christians continued that practice of table fellowship, which they came to call “Eucharist,” the Greek word for thanksgiving. At those shared tables, both then and today, Christians do two interrelated things: we remember the violence of a state-sponsored execution and we proclaim a hopeful faith in the God who brings new life from such pain and suffering.

Josiah Royce, a late-nineteenth century American philosopher of religion, described a genuine community as a people who share both memory and hope in common. People who share only memory but no hope often fall into a paralyzing despair; people who dwell on hope with no shared memory can easily drift into utopian fantasy. A genuine and indeed beloved community, Royce argued, will always share the intertwining of memory and hope. He applied this description to Christians at the Eucharistic table.

We have some daunting and likely gut-wrenching work ahead of us as Americans living in a deeply divided, fragmented, and increasingly hostile society. The wounds and scars that divide us are not new, of course, but for many white liberals like me, too many of those wounds have gone unnoticed for too long; we have not held enough memory in common and we have lived with too much untethered hopefulness.

America cannot be “great” nor can we move “forward together” without remembering more honestly and bravely how firmly our national roots are planted in a violent past, without hoping for a future in which my thriving and flourishing are inextricably bound up with yours.

The family Thanksgiving table likely cannot bear the weight of that crucial work. Perhaps that’s why our faith communities still matter – our synagogues, our churches, our mosques. Perhaps the standoff at Standing Rock can become the occasion for forging new modes of multi-faith solidarity, a fresh vision of shared tables on sacred land, a way through painful memories toward a hopeful horizon.

Perhaps so – and if so, then white Europeans will once again owe the courageous indigenous peoples of this land a profound debt of gratitude.

(Click here to support the water protectors at Standing Rock.)